Inter-rater reliability between paramedics and neurologists in the assessment of severe hemiparesis in acute stroke

Stanovení míry shody mezi záchranáři a neurology při identifi kaci těžké hemiparézy u pacientů s akutní cévní mozkovou příhodou

Cíl: Třídění pacientů záchranáři v přednemocniční péči by mohlo určit, kteří pacienti budou přímo transportováni do komplexního cerebrovaskulárního centra k provedení mechanické trombektomie. Aby třídění bylo úspěšné, zdravotničtí záchranáři musí být schopni identifikovat závažné neurologické postižení. Cílem naší studie bylo stanovit míru shody inter-rater reability mezi záchranáři a neurology – specialisty na CMP, při identifikaci těžké hemiparézy u pacientů s akutní CMP.

Metodika: V prospektivní multicentrické studii bylo využito elektronické formy výuky u 225 záchranářů Zdravotnické záchranné služby tak, aby byli schopni rozlišit lehkou a těžkou hemiparézu. Ke stanovení míry shody mezi záchranáři a neurology – specialisty na CMP v hodnocení stupně závažnosti hemiparézy (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS], body 5 a 6, skóre 0–2 [žádná nebo lehká] vs. 3–4 [těžká]) byl využit nevázaný index κ.

Výsledky: Během 10 měsíců v roce 2016 bylo v přednemocniční neodkladné péči zdravotnickými záchranáři vyšetřeno na přítomnost hemiparézy 402 pacientů (průměrný věk 75 let), kteří byli současně ihned po přijetí do iktového centra vyšetřeni také neurology – specialisty na CMP. Celková shoda mezi záchranáři a neurology při hodnocení těžké hemiparézy nebo monoparézy byla mírná: κ 0,43 (95% CI 0,36–0,50).

Závěr: V hodnocení záchranářů v přednemocniční neodkladné péči byla zjištěna mírná reprodukovatelnost identifikace těžké hemiparézy u pacientů s akutní CMP. Před zavedením změn ve směrování na základě posouzení závažnosti neurologického deficitu je zapotřebí lepšího systému vzdělávání pro záchranáře.

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Klíčová slova:

cévní mozková příhoda – třídění – zdravotnický záchranář – hemiparéza – vzdělávání

Authors:

D. Holeš 1,2; J. Král- 3 5; M. Čábal 3; D. Václavík 6; L. Klečka 7; R. Mikulík 5,8; P. Jaššo 1; M. Bar 3,4

Authors‘ workplace:

Emergency Medical Services, Moravian-Silesian Region, Czech Republic

1; Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovak Republic

2; Comprehensive Stroke Centre, University Hospital Ostrava, Czech Republic

3; Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ostrava University, Czech Republic

4; Department of Neurology, St. Anne’s University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

5; AGEL Research and Training Institute, Ostrava Vítkovice Hospital, Czech Republic

6; Primary Stroke Centre, City Hospital Ostrava, Czech Republic

7; International Clinical Research Centre, Stroke Research Programme, St. Anne’s University Hospital, Brno, Czech Republic

8

Published in:

Cesk Slov Neurol N 2019; 82(4): 391-394

Category:

Original Paper

doi:

https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2019391

Overview

Aim: Pre-hospital triage by paramedics could determine which patients qualify for direct transport to comprehensive stroke centres for mechanical thrombectomy. For triage to be successful, paramedics have to be able to identify major neurological impairments. The aim of our study was to determine inter-rater reliability between paramedics and stroke neurologists in identifying severe hemiparesis in acute stroke patients.

Methods: In this prospective, multicentre study, 225 paramedics from Emergency Medical Services were taught via e-learning to distinguish between mild and severe hemiparesis. Inter-rater agreement between paramedics and stroke specialists in evaluating the degree of hemiparesis (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS], items 5 and 6, scoring 0–2 [none or mild] vs. 3–4 [severe]) was assessed using the unweighted κ index.

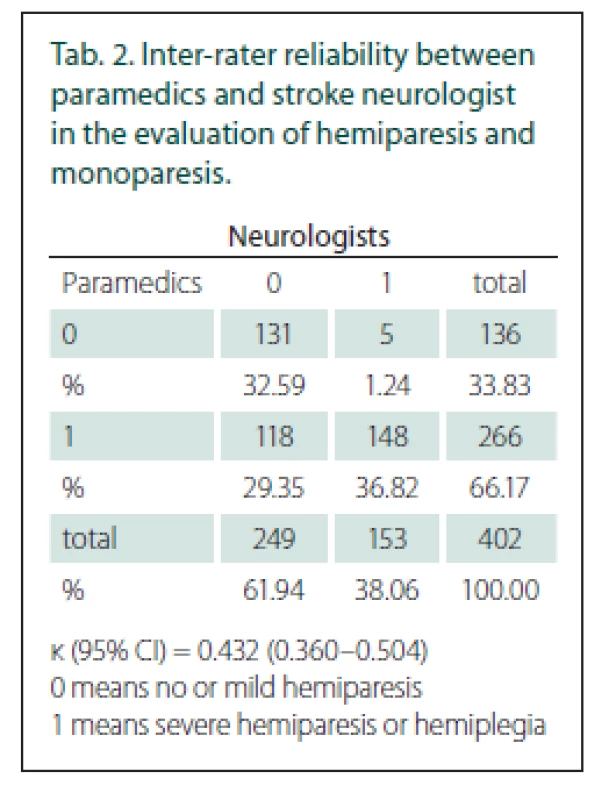

Results: Over the course of 10 months in 2016, 402 consecutive patients (average age 75 years) were evaluated for the presence of hemiparesis by paramedics during pre-hospital care and by stroke neurologists immediately after stroke centre admission. The total agreement between the paramedics and neurologists in their evaluations of severe hemiparesis or monoparesis was moderate: κ 0.43 (95% CI 0.36–0.50).

Conclusion: We found moderate reproducibility of the identification of severe hemiparesis in acute stroke patients when assessed by paramedics in a pre-hospital setting. Better education for paramedics is needed before implementing a change in transport triage based on their assessment of severity of neurological deficit.

护理人员与神经科医师在评估急性中风严重偏瘫时的可信度

目的:医护人员进行院前分诊可以确定哪些患者有资格直接转运到综合性卒中中心进行机械血栓切除术。为了成功地进行分流,护理人员必须能够识别出严重的神经损伤。我们的研究目的是确定护理人员和中风神经科医师在鉴别急性中风病人严重偏瘫时的可信度。

方法:在这项前瞻性的多中心研究中,通过电子学习对来自急诊医疗服务的225名护理人员进行了培训,以区分轻度和重度偏瘫。医护人员和中风专家之间在评估偏瘫程度方面的评估者之间达成共识(美国国立卫生研究院中风量表[NIHSS],项目5和6,得分为0–2 [无或轻度]与3-4 [严重])使用未加权的κ指数进行评估。

结果:2016年的10个月中,护理人员在院前护理期间以及卒中中心入院后立即由卒中神经病学家对402名连续患者(平均年龄75岁)进行了偏瘫评估。护理人员和神经科医生在评估严重偏瘫或单瘫时的总体共识是中等的:κ0.43(95%CI 0.36-0.50)。

结论:我们发现,在院前环境中由医护人员评估时,急性卒中患者中严重偏瘫的鉴定具有中等可重复性。在根据他们对神经功能缺损严重程度的评估对运输分类进行更改之前,需要对护理人员进行更好的教育。

关键词:中风–分诊–护理人员–偏瘫–训练

Keywords:

stroke – hemiparesis – triage – paramedics – training

Introduction

Mechanical thrombectomy (MT) significantly reduces disability in acute stroke patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke [1] and the time to MT is a very important factor for a good clinical outcome [2].

The recommendation of Mayank Goyal et al divides patients into three categories. They defined patients who benefit from direct transport to the comprehensive stroke centre (CSC) for MT despite the distance to the centre [3].

The delay of secondary transfer from a primary stroke centre to a CSC is a major factor limiting the use of MT in acute ischaemic stroke [4]. Recently, several studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between stroke deficit severity and the presence of LVO in acute ischaemic stroke patients [5–7].

Based on this evidence, it has been suggested that patients with severe neurological deficit who are suspected of having an LVO stroke should be transported directly to a CSC for MT [8,9].

The ’mothership’ model might be favoured in metropolitan areas, with transportation time to a CSC of less than 30–45 min and the use of the ’drip-and-ship’ model when transportation times are longer [10].

Paramedics therefore have to be able to distinguish between severe and mild stroke during pre-hospital care. Several stroke scales are available to make this distinction.

Severe hemiparesis and severe monoparesis have been demonstrated as the most sensitive symptoms of LVO stroke [5]. Therefore, we have implemented a simple pre-hospital stroke scale that evaluates Face Arm Speech Test (FAST) positive patients for the presence or absence of severe hemiparesis or severe monoparesis. The name of this test is the FAST PLUS test [11].

The ability of paramedics to distinguish between mild and severe hemiparesis enables changing triage from a ‘drip--and-ship’ system to a ‘drip-and-ship’ or ‘mothership’ [12].

Our previous study evaluated the specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the FAST PLUS test as administered by paramedics for LVO stroke and confirmed by CTA. Most of the LVO stroke patients (93%) had positive FAST PLUS test results, with a high sensitivity of 93% (95% CI 87–97) and NPV (94%). The specificity was 47% (95% CI 39–50) and the PPV was 41% (95% CI 35–47) [11].

The aim of our study was to identify inter--rater reliability (IRR) between paramedics and stroke neurologists for the presence or absence of severe hemiparesis or monoparesis.

Methods

This multicentre, prospective cohort, observational study assesses IRR between paramedics and stroke neurologists in neurological assessment. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03072524. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Ostrava (Ostrava, Czech Republic), approval number 82/ 2016. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Education of paramedics

In previous practice, paramedics selected suspected stroke patients according to their FAST test results. For this study, paramedics were trained via e-learning to conduct the FAST PLUS test. A total of 225 Emergency Medical Services (EMS) paramedics were taught via e-learning to distinguish between mild hemiparesis or monoparesis and severe hemiparesis or monoparesis. For their education, three video recordings were used to demonstrate the motor deficit examination of lower and upper limbs. The first video shows a patient with complete hemiparesis; the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 4 for both limbs. The second video shows a patient with severe hemiparesis, with an NIHSS score of 3 for both limbs. The third video shows a patient with mild hemiparesis, with an NIHSS score of 2 for both limbs. All paramedics had to go through e-learning; this was verified by the use of the paramedic’s personal password; the e-learning was not followed by any exam.

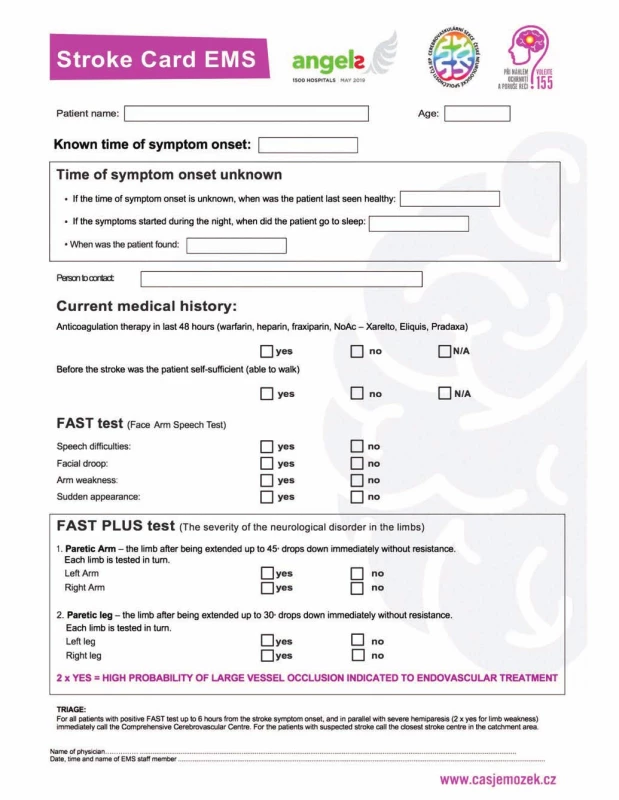

A severe stroke is defined as a patient with severe unilateral hemiparesis (NIHSS 3 or 4 points in items 5 and 6) or monoparesis (NIHSS 3 or 4 points in item 5). Such patients have been identified as FAST PLUS test positive, because the paramedics identified them as FAST positive and then as having severe or mild hemiparesis. The results of the FAST PLUS test are part of the Stroke Card that paramedics use; see Fig. 1.

Obr. 1. Iktová karta a FAST PLUS test

Eight certificated stroke neurologists participated in our study. All of them were trained in NIHSS examination (certified).

Study population

All consecutive suspected stroke patients (FAST test positive) from the primary catchment area of three stroke centres (637,584 inhabitants) – University Hospital Ostrava, City Hospital Ostrava, and Vítkovice Hospital Ostrava – were examined by paramedics during pre-hospital care and by stroke specialists (using the NIHSS at the emergency stroke ward just after admission).

Data collection

We used the following data in our evaluation: Stroke Card and FAST PLUS test, age, gender, non-contrast CT, CTA, NIHSS score on admission, time between paramedic and stroke specialist examination, NIHSS for arms and NIHSS for legs.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, Stata version 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the unweighted κ index. Agreement was considered ‘poor’ at κ < 0.4, ‘moderate’ at 0.41–0.60, ‘substantial’ at 0.61–0.80, and ‘almost perfect’ at > 0.81.

Results

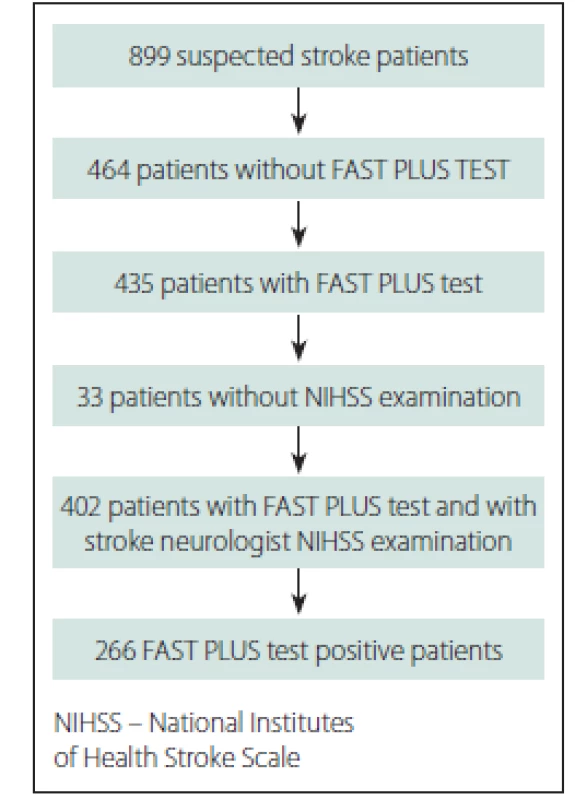

Over the course of 10 months in 2016, 899 suspected stroke patients were transported within 12 h of stroke onset to three stroke centres in Ostrava, a city in the Moravian-Silesian region with a catchment area of 637,584 inhabitants.

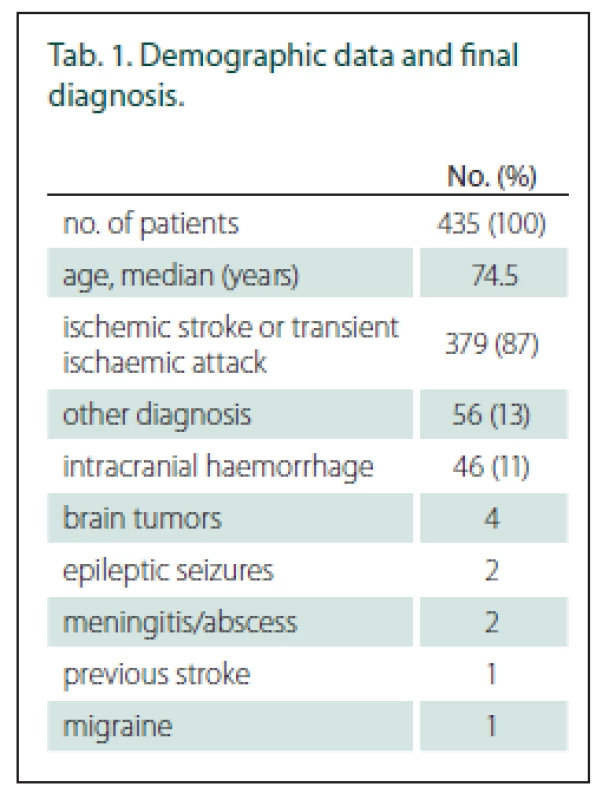

Of those suspected stroke patients, 435 patients were examined by paramedics; 402 of those patients were evaluated for the presence of hemiparesis by paramedics during pre-hospital care and by stroke neurologists immediately after stroke centre admission (Fig. 2). The baseline data and final diagnosis are shown in Tab. 1. The average NIHSS score was 8.6 (0–33) according to stroke neurologists just after stroke centre admission. The time between the paramedics’ and the stroke specialists’ examinations was median 42 min (IQR 24 min).

Obr. 2. Vývojový diagram účastníků.

0 means no or mild hemiparesis<{r>

1 means severe hemiparesis or hemiplegia

Out of the 402 patients who received both evaluations, 266 (66%) had severe hemi - or monoparesis according to the paramedics’ examination (FAST PLUS positive) and 153 (38%) according to the neurologists’ examination. The total agreement between the paramedics and neurologists in evaluating severe hemiparesis or monoparesis was moderate, with a κ value of 0.43 (95% CI 0.36–0.50) (Tab. 2). LVO was found in 124 patients (31%). The main reason for disagreement was the overstatement of the degree of hemiparesis by the paramedics in 118 patients. In five patients, hemiparesis was underestimated.

Discussion

The evaluation of stroke severity during the pre-hospital stage of care is very important for triage of acute stroke patients.

Patients who demonstrate any signs of stroke (FAST test positive) should then undergo a second screen using a tool validated to assess stroke severity, which may be considered in decisions for transportation destination [9].

Our study assessed stroke severity according to the presence of severe hemiparesis or monoparesis (NIHSS items 5 and 6 scoring 3 or 4) only.

After the paramedics were educated via e-learning in the screening of stroke patients (FAST test) and in the presence of severe mono - or hemiparesis (FAST PLUS test), we reached moderate agreement with a κ of 0.43 between paramedics and neurologists in evaluating arm motor deficit or both arm and leg motor deficit. Several stroke scales evaluate acute stroke patients.

The FAST test evaluates three items (face drooping, arm weakness and speech difficulties); it is the most widely used scale in pre-hospital care for predicting stroke except LVO stroke. In a previous study, the FAST test showed good agreement with the physician’s assessment; the highest prevalence was found in arm weakness (κ = 0.77) [13].

The NIHSS can best identify the severity of stroke [12]. Excellent agreement (κ 0.84 and 0.88, resp.) was found between neurologists in the NIHSS evaluation of mono - or hemiparesis (items 5 and 6) [14]. However, the NIHSS is too complex and time-consuming to be used by pre-hospital EMS.

Other studies with easier stroke scales designed for paramedics evaluated the screening of stroke patients or the relation between stroke severity and LVO stroke [15–21]. Only three studies have evaluated stroke scales (Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation [RACE], Cincinnati Stroke Triage Assessment Tool [C-STAT] and Los Angeles Motor Scale [LAMS]) prospectively or in the field [21–24].

Our results are comparable to those of the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS).

The CPSS is a three-item scale which assesses arm weakness, speech difficulties and facial droop.

Kothari et al published Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: Reproducibility and Validity, evaluating IRR between paramedics and stroke specialists. In their study, 49 stroke patients were examined by paramedics at the emergency ward, not pre-hospital. IRR in this study ranged from κ 0.85 (motor arm deficit) to 0.39 (facial palsy) [23].

Ferguson et al presented their evaluation of IRR of the LAMS. The LAMS evaluates three items: facial droop, arm drift and grip strength. They reached a cumulative κ of 0.83 (excellent) but only between paramedics, not between paramedics and neurologists [24]. The most extensive pre-hospital data are provided by the RACE scale. This score validates a five-item scale (facial palsy, arm motor function, leg motor function, head and gaze deviation and aphasia/ agnosia). A study of the RACE test has data from 357 patients, but inter-rater variability of the RACE test has not been published [21].

In our study, severe hemi - or monoparesis was diagnosed in 266 patients by paramedics and in 153 patients by neurologists. LVO was found in 124 patients (31%). Of this group of patients 115 patients were FAST PLUS test positive, and 9 patients were FAST PLUS test negative [11].

We evaluated the reason for this disagreement according to written descriptions of hemiparesis. The main reason for disagreement was the overstatement of the degree of hemiparesis by paramedics in 118 patients.

It is possible that the patients’ clinical status changed during the time between the paramedics’ and the neurologists’ examinations (median 42 min).

Paramedics overstating the degree of hemiparesis could lead to incorrect triage of acute stroke patients, which could delay the start of intravenous thrombolysis treatment. A high number of false positive patients could cause an overloading of CSC with patients who are not suitable for MT. Therefore, further training of paramedics is necessary, using not only e-learning but also standardized video testing and certification.

The limitations of our study

The time delay between the assessments of the paramedics and that of the stroke physicians could lead to bias due to transient ischaemic attack or regressing stroke; this is a major limitation of our study.

The paramedic training was conducted only via the internet, without further testing or feedback.

The accuracy, IRR and quality of the physicians’ assessments were not analysed in this study.

Conclusion

Our study found that even identifications of typical stroke symptoms such as severe paresis or hemiparesis had moderate reproducibility when assessed in pre-hospital settings by paramedics. Before any pre-hospital stroke scale to triage stroke patients is implemented into clinical routine care, better educational methods should be developed such as using standardized video testing and certification.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Assoc. Prof. Michal Bar, MD, PhD

Comprehensive Stroke Centre University Hospital Ostrava

17. listopadu 1790

708 52 Ostrava

Czech Republic

e-mail: michal.bar@fno.cz

Accepted for review: 17. 3. 2019

Accepted for print: 11. 6. 2019

Sources

1. Goyal M, Menon BK, Van Zwam WH et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016; 387(10029): 1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(16)00163-X.

2. Saver JL, Goyal M, Van der Lugt AA et al. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Jama 2016; 316(12): 1279–1288. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2016.13647.

3. Goyal M, Menon BK, Wilson AT et al. Primary to comprehensive stroke center transfers: Appropriateness, not futility. Int J Stroke 2018; 13(6): 550–553. doi: 10.1177/ 1747493018764072.

4. Prabhakaran S, Ward E, John S et al. Transfer delay is a major factor limiting the use of intra-arterial treatment in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011; 42(6): 1626–1630. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.110.609750.

5. Nakajima M, Kimura K, Ogata T et al. Relationships between angiographic findings and National Institutes of Health stroke scale score in cases of hyperacute carotid ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25(2): 238–241.

6. Fischer U, Arnold M, Nedeltchev K et al. NIHSS score and arteriographic findings in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2005; 36(10): 2121–2125. doi: 10.1161/ 01.STR.0000182099.04994.fc.

7. Scheitz JF, Abdul-Rahim AH, MacIsaac RL et al. Clinical selection strategies to identify ischemic stroke patients with large anterior vessel occlusion. Stroke 2017; 48(2): 290–297. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.116.014431.

8. Ahmed N, Steiner T, Caso V et al. Recommendations from the ESO-Karolinska stroke update conference, Stockholm 13–15 November 2016. Eur Stroke J 2017; 2(2): 95–102. doi: 10.1177/ 2396987317699144.

9. Boulanger JM, Lindsay MP, Gubitz G et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations for acute stroke management: prehospital, emergency department, and acute inpatient stroke care, update 2018. Int J Stroke 2018; 13(9): 949–984. doi: 10.1177/ 1747493018786616.

10. Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U et al European Stroke

Organisation (ESO) – European Society for Minimally Inva-

sive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) Guidelines on mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11(6): 535–538. doi: 10.1136/ neurintsurg-2018-014569.

11. Václavík D, Bar M, Klečka L et al. Prehospital stroke scale (FAST PLUS Test) predicts patients with intracranial large vessel occlusion. Brain Behav 2018; 8(9): e01087. doi: 10.1002/ brb3.1087.

12. Michel P. Prehospital scales for large vessel occlusion: closing in on a moving target. Stroke 2017; 48(2): 247–249. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.116.015511.

13. Nor AM, McAllister C, Louw SJ et al. Agreement between ambulance paramedic-and physician-recorded neurological signs with Face Arm Speech Test (FAST) in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2004; 35(6): 1355–1359. doi: 10.1161/ 01.STR.0000128529.63156.c5.

14. Dewey HM, Donnan GA, Freeman EJ et al. Interrater reliability of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale: rating by neurologistsand nurses in a community-based stroke incidence study. Cerebrovasc Dis 1999; 9(6): 323–327. doi: 10.1159/ 000016006.

15. Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989; 20(7): 864–870.

16. Lima FO, Silva GS, Furie KL et al. Field assessment stroke triage for emergency destination. Stroke 2016; 47(8): 1997–2002. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.116.013301.

17. Hastrup S, Damgaard D, Johnsen SP et al. Prehospital Acute Stroke Severity scale to predict large artery occlusion. Stroke 2016; 47(7): 1772–1776. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.115.012482.

18. Katz BS, McMullan JT, Sucharew H et al. Design and validation of a prehospital scale to predict stroke severity. Stroke 2015; 46(6): 1508–1512. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.115.008804.

19. Singer OC, Dvorak F, de Rochemont RD et al. A Simple 3-Item Stroke Scale. Stroke 2005; 36(4): 773–776. doi: 10.1161/ 01.STR.0000157591.61322.df.

20. Nazliel B, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS et al. A brief prehospital stroke severity scale identifies ischemic stroke patients harboring persisting large arterial occlusions. Stroke 2008; 39(8): 2264–2267. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.107.508127.

21. Pérez de la Ossa N, Carrera D, Gorchs M et al. Design and validation of a Prehospital Stroke Scale to predict large arterial occlusion. Stroke 2014; 45(1): 87–91. doi: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.113.003071.

22. McMullan JT, Katz B, Broderick J et al. Prospective prehospital evaluation of the cincinnati stroke triage assessment tool. Prehosp Emerg Care 2017; 21(4): 481–488. doi: 10.1080/ 10903127.2016.1274349.

23. Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T et al. Cincinnati prehospital stroke scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 33(4): 373–378.

24. Ferguson KN, Kidwell CS, Starkman S et al. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS), a prehospital measure of stroke severity. Stroke 2002; 33(1): 384–384.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery NeurologyArticle was published in

Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2019 Issue 4

-

All articles in this issue

- Intracranial stenosis – the best conservative treatment should be combined with a stent - YES

- Intracranial stenosis – the best conservative treatment should be combined with a stent - NO

- Intracranial stenosis – the best conservative treatment should be combined with a stent

- Multiple system atrophy

- Two original Czech tests for memory evaluation in three minutes – Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (ALBA)

- Hypersomnia in acute bilateral thalamic ischemic stroke

- Hearing loss after spinal anesthesia

- Superior semicircular canal dehiscence

- The spectrum of MRI findings of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis in the Czech Republic

- Sense of smell examination before and after surgery for nasal polyposis

- Retrospective autoevaluation of the results of intrinsic brain tumor surgeries – consecutive cohort of 270 surgeries within one neurosurgical center of the NOS ČOS (Neurooncological section of the Czech Oncology Society) from 2015–2017

- Spina bifida in the Czech Republic – incidence and prenatal diagnostics

- Intrathecal baclofen pump for the treatment of severe spasticity – 15 years of experience

- Behavioral manifestation profi le in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder

- Effect of subcutaneously administered interferon β-1a on disease activity in patients with clinically isolated syndrome – ATRACT observational study

- Is it necessary to perform irrigation of a haematoma during the operation of a chronic subdural haematoma via burr hole drainage?

- Inter-rater reliability between paramedics and neurologists in the assessment of severe hemiparesis in acute stroke

- Olfactory dysfunction in a cohort of Czech patients with idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder

- Giant frontal sinus pneumocele with massive intracranial spread imitating lumboperitoneal shunt malfunction in a predisposed patient with Marfan syndrome

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Multiple system atrophy

- Superior semicircular canal dehiscence

- Spina bifida in the Czech Republic – incidence and prenatal diagnostics

- Hearing loss after spinal anesthesia