Severe Serotonin Syndrome

Závažný serotoninový syndrom

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Authors:

M. Káňová 1; J. Ďuricová 2,3; J. Slonková 4; V. Marcián 4; P. Ševčík 1,5

Authors‘ workplace:

University Hospital Ostrava, Czech

; Republic

Department of Anaesthesiology and

Republic

Intensive Care Medicine

1; Republic

Institute of Clinical Pharmacology

2; Republic

Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of

Republic

Medicine, University of Ostrava

3; Republic

Department of Neurology

4; Republic

Department of Intensive Medicine

Republic

of Emergency Medicine and Forensic

Republic

Studies, Faculty of Medicine, University

Republic

of Ostrava

5

Published in:

Cesk Slov Neurol N 2017; 80(6): 711-713

Category:

Letter to Editor

doi:

https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2017711

Overview

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Dear Editors,

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition. It results from excessive serotonin effect on the central and peripheral nervous system. Serotonin (5-HT) is an excitatory neurotransmitter involved in the regulation of wakefulness, affective behaviour, and regulation of autonomic functions such as vascular tone, gastrointestinal motility and thermoregulation [1,2].

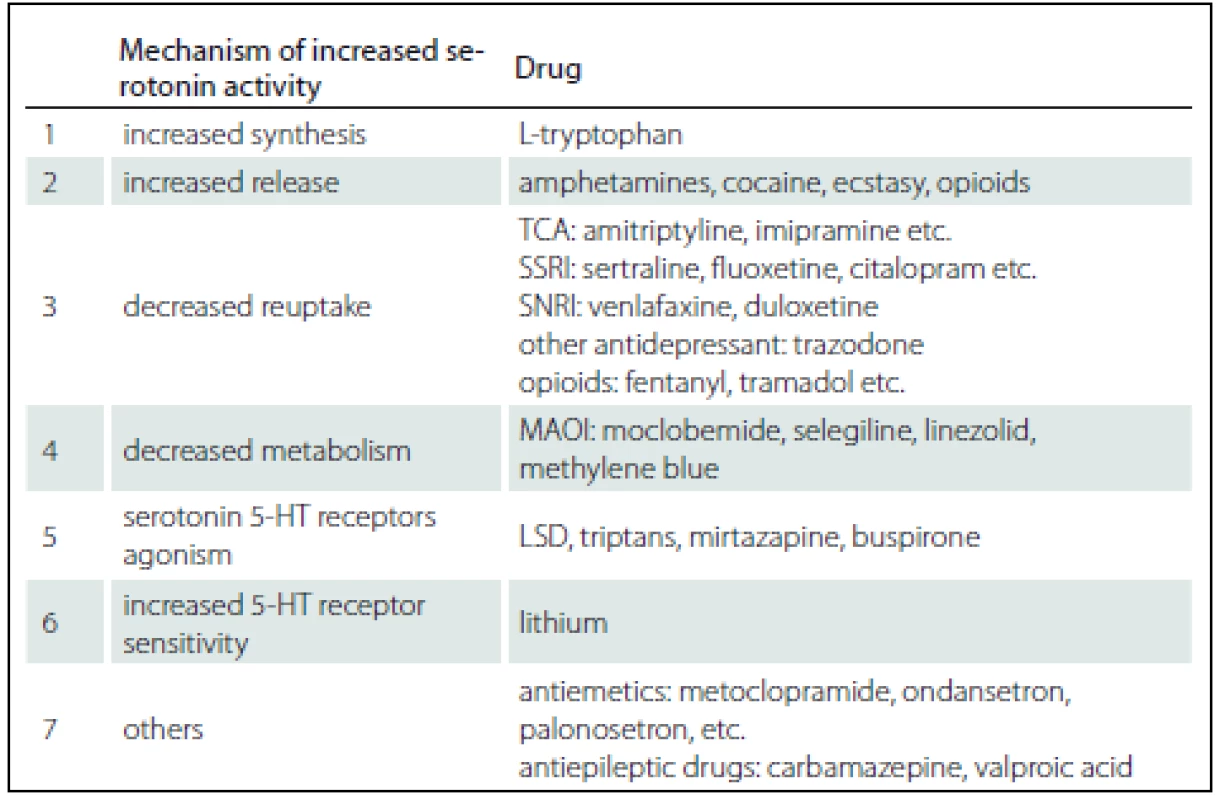

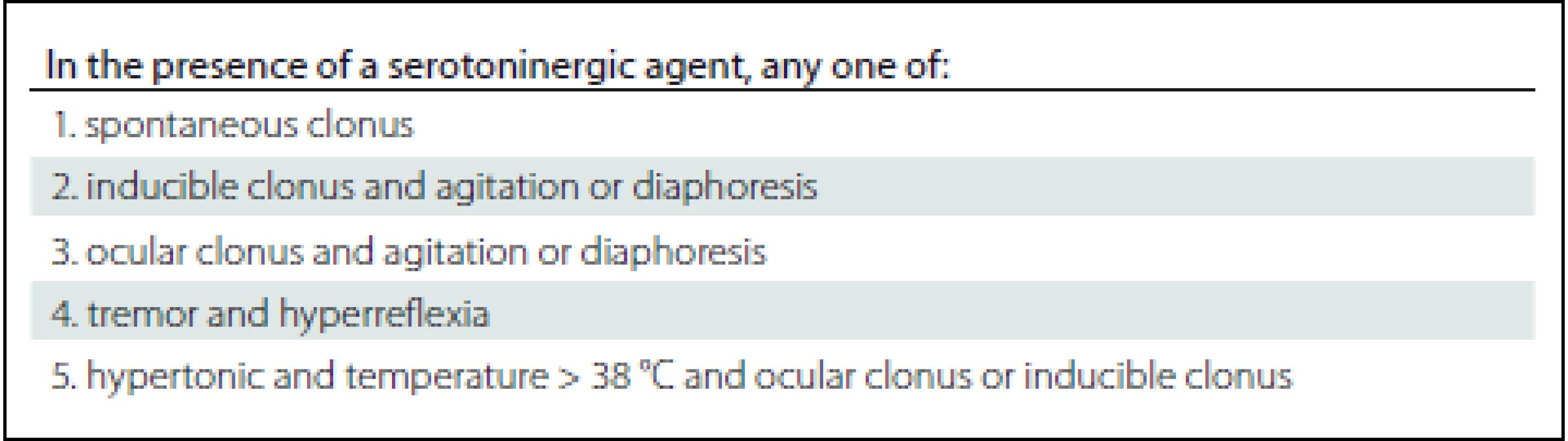

The onset of SS ranges from several hours to several weeks after the administration of serotonergic drugs (Tab. 1). SS is difficult to detect as the signs can run from mild to lifethreatening symptoms involving mental status changes (anxiety, agitation, visual hallucinations, restlessnes , disorientation and coma), autonomic instability (hyper-/ hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, diarrhea, mydriasis, hyperthermia) and neuromuscular hyperactivity (muscle rigidity, tremors, nystagmus, myoclonus, ocular clonus, hyperreflexia). Several diagnostic criteria have been published (Sternbach’s Criteria, Radomski’s Criteria and more sensitive and specific Hunter’s Criteria in Tab. 2). The seven clinical features are associated with serotonin toxicity: clonus, agitation, diaphoresis, tremor, hyperreflexia and hypertonicity with temperature > 38 °C [2 – 4]. Mild symptoms usually resolve within 24 hours of cessation of the serotonergic drugs. Severe cases may manifest assevere hyperthermia, seizure, rigidity, respiratory arrest, or even death [1,5]. No specific laboratory abnormality is diagnosed in SS. The blood level of serotonin does not correlate with the severity of the condition as it does not refl ect the intrasynaptic serotonin level. In cases of severe serotonin toxicity with muscular hypertonicity and rhabdomyolysis we can observe electrolyte derangements, metabolic acidosis, elevated creatinine levels and increased serum aminotransferase [4,6].

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are the most frequently reported drugs associated with SS. When SS is recognised, im mediate withdrawal of the causative drug is necessary. Supportive care is the mainstay of the treatment. Anxiety and agitation can be managed with benzodiazepines and serotonin symptoms can be managed with the 5-HT1A/ 2A receptor antagonist cyproheptadine or chlorpromazine. Severe cases of hyperthermia may require neuromuscular paralysis and intubation. Antipyretic agents do not help, because hyperthermia is caused by muscle hypermetabolism. Only early diagnosis and treatment can prevent complications such as the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death [1,2,6].

A 51-year-old female was presented to our emergency department early in the morning for dyspnoea, significant arthralgia, psychomotor unrest, and tremor. Physical examination showed mydriasis, tachycardia (110/ min), arterial hypertension (160/ 100 m m Hg), elevated respiratory rate (24/ min) and raised temperature (39 °C). According to the medical history, the patient had been repeatedly prescribed analgesic drugs (meloxicam, indomethacin and tramadol). She had asthma bronchiale treated with the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide in fixed combination with formoterol (160/ 4.5 mg). Further medication of the patient included ivabradine (10 mg/ d) for sinus tachycardia, psychiatric medications paroxetine (60 mg/ d), trazodone (300 mg/ d), chlorprothixen (50 mg/ d) and bromazepam (2 mg/ d). According to the patient’s medical history confirmed lately by a family member, the patient was virtually housebound due to pain. She combined various analgesics and antidepressants, 2 days before admission she had even increased doses by herself. During the examination, the patient suffered from a collapse. An electromechanical dissociation was diagnosed and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated (lasting for 5 min). Severe metabolic acidosis was found. A nasogastric tube was passed and showed the presence of a variety of drugs in the stomach contents. Samples for toxicological testing were sent. The electrocardiography (ECG) showed 0.5 - mm ST segment depression in I and aVL leads. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was negative for pulmonary embo lisms, while CT of the brain demonstrated an oedema.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after CPR for asystole of unclear aetiology. On admission, sedation (sufentanil, midazolam) and artificial pulmonary ventilation were started and rescue ther apy was initiated. We observed significant circulatory instability combined with sinus tachycardia (up to 160/ min) and administered high doses of norepinephrine and esmolol. The level of leukocytes was 20,000. Blood and urine samples were sent for cultivation. Additionally, antimicrobial agents were administered (levofloxacin, piperacillin/ tazobactam) and anti-oedematous therapy (osmother apy with 10% NaCl) was applied to reduce cerebral oedema. Facial myoclonus was observed as well as subsequent spasms of the entire body. Electroencephalography (EEG) revealed nonspecific epileptic graphoelements. Higher doses of benzodiazepines (midazolam 15 mg/ h) were required to manage persisting generalized myoclonus. A neuro-blocking agent – cisatracurium (20 mg) – was administered due to the interference with artificial ventilation. The initial pH after admission to our ICU was 7.1, BE 14.6 with lactate 20 mmol/l. We started with differential diagnosis of severe metabolic acidosis. Testing for ethanol, methanol and ketones showed negative results, renal functions were normal. Toxicological testing for antidiabetic drugs was negative, but the presence of many substances: analgesic drugs (codeine, tramadol, meloxicam and acetaminophen), antidepressants (trazodone, paroxetine), anxiolytic drugs (hydroxyzine, midazolam) and chlorprothixen, was confirmed. The patient was continuously febrile, requiring sedation (midazolam 10 – 15 mg/ h and sufentanil 10 μg/ h) and physical cooling, but the effect was disputable. Antipyretics (acetaminophen, 4 g/day) were ineffective.

By day 2, the patient’s serum laboratory fidings showed an increased leucocytosis (30,000). She developed oliguria, serum myoglobin levels reached 14.434 mg/ l during the day, and therefore, continuous renal replacement ther apy (CRRT) was initiated. The laboratory evaluation excluded a systemic disease. She developed pneumonia (Candida albicans and Aspergilus fumigatus) and voriconazole was added to the treatment.

By day 4, her white blood cell count started to decrease, the metabolic acidosis resolved, but myoglobinaemia decreased only slowly. However, the patient’s circulatory system was still unstable. A transcranial Doppler (TCD) showed no signs of intracranial hypertension. Electroencephalography was performed repeatedly, generalized triphasic waves were observed, but without specific epileptic discharges (Fig. 1). Tracheostomy was performed and sedation was subsequently reduced. Finally, on day 5-serotonin syndrome was diagnosed in cooperation with clinical pharmacologist and neurologists. The clinical triad characteristic for SS was confirmed: mental changes prior to sedation (agitation, delirium), vegetative instability (sweating, fever, tachycardia) and myoclonus accompanied by rhabdomyolysis and muscular rigidity. New potential serotonergic drugs were stopped (opioid agent sufentanil and prokinetic agent metoclopramide, antibiotic levofl oxacin - inhibitor CYP3A4), benzodiazepines continued and anti-serotonergic ther apy (chlorpromazine plus cyproheptadine) were initiated. An initial dose of 12 mg of cyproheptadine was administered and then 2 mg every 2 h to a max. dose of 32 mg/ day. Maintenance dosing of 8 mg every 6 h was administered on the following days. The patient’s clinical condition improved. However, the long-term prognosis was very unfavourable and 16 days later the patient appeared as coma vigil.

Severe SS toxicity may develop into a life-threatening condition with muscular rigidity, hyperthermia and coma. Symptoms with escalating toxicity, if left untreated, may result in complications including metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, seizures and death [2]. The case report detailed above is an example of a severe case of SS which developed into coma vigil due to an untimely diagnosis of the condition. The patient’s medical history as well as serum toxicological analysis revealed the presence of several serotonergic drugs, antidepressants (trazodone, paroxetine) and analgesics (tramadol, codeine) [3,4]. Antidepressants may be the most commonly implicated drugs associated with SS [7–9]. The lack of monitoring of the potential iatrogenic adverse interactions was a significant factor for the untimely diagnosis of SS.

The presented case demonstrates the necessity to consider drug interactions. It is highly challenging for clinicians to identify therapeutic combinations that may increase the risk of SS. Serotonin toxicity presents as a triad of symptoms of mental-status changes, autonomic hyperactivity and neuromuscular abnormalities. Early recognition of SS and discontinuation of offending drugs are vital for successful management of this serious adverse reaction.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

MUDr. Marcela Káňová

Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine University Hospital Ostrava

17. listopadu 1790

708 52 Ostrava-Poruba

Czech Republic

e-mail: marcela.kanova@fno.cz

Accepted for review: 2. 4. 2017

Accepted for print: 16. 10. 2017

Sources

1. Prokeš M, Suchopár J. Serotoninový syndrom: co bychom o něm měli vědět. Med praxi 2014;11(5):226 – 30.

2. Rastogi R, Swarm RA, Patel TA. Case scenario: Opiod association with serotonin syndrome, im-plications to the practitioners. Anesthesiology 2011;115 : 1291 – 8. doi: doi:10.1097/ ALN.0b013e31823940c0.

3. Cooper BE, Sejnowski CA. Serotonin syndrome: recognition and treatment. AACN Adv Crit Care 2013;24(1): 15 – 20. doi: 10.1097/ NCI.0b013e31827eecc6.

4. Mohr P. Serotoninový syndrom – diagnostika, terapie, prevence. Psychiatr prax 2001;3 : 117 – 20.

5. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148(6):705 – 13. doi: 10.1176/ ajp.148.6.705.

6. Ables AZ, Nagubilli R. Prevention, diagnosis and management of serotonin syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2010;81(9):1139 – 42.

7. Sato Y, Nakamura K, Yasui-Furukori N. Serotonin syndrome induced by the readministration of escitalopram after a short-term interruption in an elderly woman with depression: a case report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015;11 : 2505 – 7. doi: 10.2147/ NDT.S92081.

8. Prakash S, Belani P, Trivedi A. Headache as a presenting feature in patients with serotonin sydrome: a case series. Cephalalgia 2014;34(2):148 – 53. doi: 10.1177/ 0333 102413495968.

9. Lamberg JJ, Gordin VN. Serotonin syndrome in a patient with chronic pain polypharmacy. Pain Med 2014;15(8):1429 – 31. doi: 10.1111/ j.1526-4637.2012.01468.x.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery NeurologyArticle was published in

Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2017 Issue 6

-

All articles in this issue

- The Utilisation of Ultrasound for Navigation in Neurosurgery

- H-reflex and Its Role in EMG Laboratory and Clinical Practice

- State-of-the-Art MRI Techniques for Multiple Sclerosis

- Case of Early Neurosyphilis with Neurocognitive Impairment

- Peripheral Facial Paresis Linked to Air Travel

- AMETYST – Results of an Observational Phase IV Clinical Study Evaluating the Effect of Intramuscular Interferon Beta-1a Therapy in Patients with Clinically Isolated Syndrome or Clinically Definite Multiple Sclerosis

- Assessment of Life Satisfaction in Patients with Clinically Isolated Syndrome

- Brief Test of Verbal Memory Using the Sentence in Alzheimer Disease

- When to Operate on Temporal Bone Fractures?

- Vascular Non-hemorrhagic Complications of Deep Brain Stimulation

- The Effects of Robotic Gait Rehabilitation on Psychosomatic Indicators at the People with Different Etiology of Mental Retardation

- Predictors of Good Clinical Outcome in Patients with Acute Stroke Undergoing Endovascular Treatment – Results from CERBERUS

- Quantitative MRI Texture Analysis in Differentiating Enhancing and Non-enhancing T1-hypointense Lesions without Application of Contrast Agent in Multiple Sclerosis

- Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome

- Severe Serotonin Syndrome

- Baclofen and Clonazepam Overdose in a Patient with Chronic Neck and Shoulder Pain

- A Novel Mutation in the GIGYF2 Gene in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease

- Frameless Image-guided Stereotactic Brain Biopsy – Advantages, Limitations, and Technical Tips

- Dermatomyositis – Initial Manifestation of Advanced Stage Primary Signet Ring Cell Ovarian Carcinoma

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Brief Test of Verbal Memory Using the Sentence in Alzheimer Disease

- State-of-the-Art MRI Techniques for Multiple Sclerosis

- H-reflex and Its Role in EMG Laboratory and Clinical Practice

- When to Operate on Temporal Bone Fractures?